Today, the Center for Online Safety and Liberty (COSL) filed an amicus curiae (friend of the court) brief in United States v. Steven Anderegg in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. This case matters far beyond the parties. It goes to a question with consequences for artists, readers, queer and trans communities, survivors, and frankly anyone who keeps books, comics, or a hard drive: can the government throw you in prison for fictional or fantasy content that you privately create or possess at home, simply by labeling it “obscene”? Our position is no—and we’ve asked the court to draw a bright constitutional line.

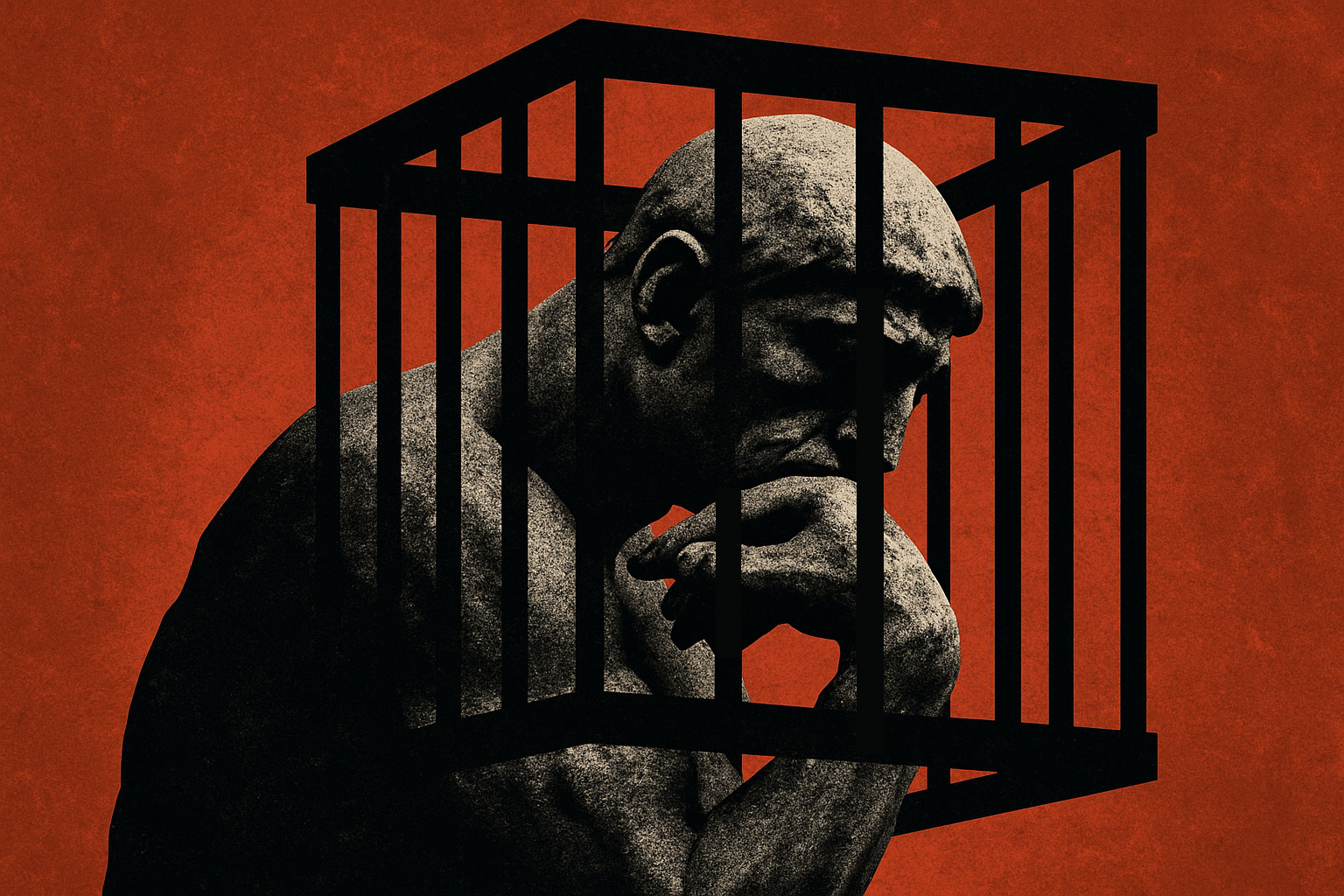

At the heart of the appeal is a bedrock principle from a 1969 case Stanley v. Georgia: the state cannot criminalize the private possession of obscene material in the home. That right protects “the right to receive information and ideas” and to be free “from unwanted governmental intrusions” into private life. COSL’s brief explains why that principle applies here, and why attempts to criminalize the private production of virtual material go even further, threatening to punish thought itself.

Why this case is so important right now

If this were just about one defendant, it wouldn’t make our front page. It’s about the bigger project we’re seeing from some lawmakers and prosecutors to expand “obscenity” until it swallows everything they don’t like, then use that label to police culture and private life.

Consider three examples that show the trend line:

- Texas SB 20 (2025) created a new felony for possessing or promoting any obscene visual material that appears to depict a minor—even if it’s a drawing, animation, or AI image (i.e., no real child is involved). That’s a sea change toward criminalizing fantasy and fiction.

- Oklahoma SB 593 (2025) proposed a brand-new category called “unlawful pornography,” sweeping in an enormous range of sexual content—including consensual adult sexting—and would have criminalized buying, viewing, or possessing it, with penalties up to 10 years and heavy fines. (Yes, possession by adults.) It also created private “bounty” lawsuits and ratcheted penalties for “trafficking.” The bill didn’t pass, but it shows how far some are willing to go to make possession itself a felony.

- Michigan HB 4938 (2025) goes even further by explicitly targeting trans expression. The bill classifies as “prohibited material” not just a broad array of sexual content (including written and audio works), but also any depiction with “a disconnection between biology and gender”—effectively labeling depictions of trans people (and likely drag) as obscene-like contraband for all ages. It even mandates ISP filtering and blocking of VPNs and similar tools. This is not about minors; it is a full-scale content ban.

Put those together and you see the playbook: redefine “obscenity” or create adjacent categories to criminalize content that has long been protected when no real person is harmed—often with explicit carve-outs aimed at queer and trans communities.

Overlay this with efforts at the federal level to cement a nationwide obscenity definition for the internet, such as Senator Mike Lee’s Interstate Obscenity Definition Act, pitched as a way to make prosecutions easier across state lines, and you get the picture: a coordinated push to let governments decide what adults are allowed to read, draw, write, or watch—even at home.

The line we’re asking the court to draw

Our brief urges the Seventh Circuit to affirm the district court’s dismissal of a possession charge and to hold that prosecuting private production of virtual material under 18 U.S.C. § 1466A violates core constitutional protections. The logic is straightforward:

- Stanley protects private possession in the home. That protection is content-neutral: the government may regulate public distribution, but it can’t criminalize what you keep on your bookshelf or your hard drive.

- Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition makes clear that virtual depictions that do not involve real children remain protected speech. Extending criminal penalties to the creation of virtual material—drawings, writing, digital art—collapses that line and chills protected expression.

- Criminalizing private creation inside the home crosses into policing thought itself. The First Amendment doesn’t let the government punish an idea because it is offensive; the home is a constitutional sanctuary for intellectual autonomy.

- Treating virtual content the same as crimes that harm real children also triggers proportionality concerns. Where no real person is harmed, imposing severe sentences modeled on child-exploitation offenses is grossly out of step.

This isn’t an abstract debate. If courts bless prosecutions for private possession or creation of “obscene” virtual works, it will embolden the kind of laws we’re already seeing—laws that would criminalize not just pornography, but also trans representation, queer art, fan fiction, and other creative works. And it will shift enforcement into the most intimate space of all: your home computer. That is the “new line” we cannot allow to be crossed.

The power of unsympathetic defendants

Like Barry Coty, whose case in Denmark we reported on previously, the defendant in this case Steven Anderegg is accused of creating AI images of simulated children in sexually explicit poses. Unlike the charges against Coty which related to distributing such images, the charges against Anderegg (at least, those that our brief is concerned with) are for possessing such images privately. Even so, Anderegg is not going to be a popular figurehead for the civil liberties causes that his case turns upon.

Let’s be candid: sometimes the government picks the most unsympathetic defendant it can find to move the goalposts for everyone else. That’s not new. In 2021, for example, a Texas man named Thomas Alan Arthur received a 40-year federal sentence tied largely to text stories that jurors found obscene. Forty years—longer than Ghislaine Maxwell’s sentence for sex trafficking. If you think these prosecutions won’t be used to ratchet up penalties against speech next time, think again.

Courts are supposed to be the brake on this cycle. They’re where we insist that constitutional rules apply even (especially) when the speech is unpopular and the speaker is easy to dislike. Because once the precedent is set, it doesn’t only apply to “them”—it applies to all of us.

Part of COSL’s “Drawing the Line” project

This amicus is one brick in a larger effort we call Drawing the Line Between Personal Expression and Lived Abuse. The project pushes back against political attempts to blur the boundary between real harm and fictional depictions, and it’s rooted in three core commitments:

- Safety through clarity, not panic: Politicians often reach for blunt, fear-driven policies—age-verification mandates, censorship regimes, or bans on “unlawful pornography”—instead of addressing the actual conditions that allow abuse to persist. By blurring the lines between lived abuse and fictional expression, they offer the public a false sense of safety while eroding basic freedoms.

- Justice for real survivors: Survivors deserve more than slogans. When lawmakers inflate statistics by folding in fictional or virtual material, they distort the reality of abuse and divert resources from trauma-informed, survivor-centered responses. Real children are not helped when political grandstanding takes priority over evidence-based solutions.

- Protection for creative expression: Writers, artists, and digital creators are increasingly targeted as lawmakers expand obscenity and child-exploitation laws into realms of fantasy and fiction. This puts storytellers, fan communities, and even LGBTQ+ representation at risk of criminalization—not because their work causes harm, but because it challenges cultural norms.

Blunt instruments like device-scanning mandates, age-verification dragnets, and “obscenity” expansion thrive in environments of moral panic, tech illiteracy, and political pressure. COSL’s mission has always been to push back with evidence-based policy and practical safety interventions—without sacrificing the freedoms that make safer, more inclusive communities possible.

What a win would mean—and what happens if we lose

Our brief asks the Seventh Circuit to affirm dismissal of the possession count and to hold § 1466A unconstitutional as applied to private production of virtual content. That’s not a radical ask—it is an application of long-settled First and Fourth Amendment principles that are now at risk of being overridden.

A win would reaffirm a crucial boundary: the state does not get to police your private thoughts or the private creations you keep at home. It would also steer prosecutors away from using § 1466A to criminalize virtual, victimless content—and away from theories that collapse Free Speech Coalition into an all-purpose obscenity cudgel. It tells lawmakers flirting with bans on broad swaths of adult content that they cannot bootstrap criminal possession by rebranding fiction as harm.

If we lose, the chilling effect won’t be hypothetical. We’ll see more bills like Texas SB 20 (criminalizing possession of visual material that merely appears to depict a minor, even in cartoons or AI), copy-and-paste “obscene/unlawful pornography” frameworks like Oklahoma’s SB 593 (where possession becomes a felony for adults), and sweeping content bans like Michigan’s HB 4938 that fold trans depictions into “prohibited material.” That’s not a parallel universe—it’s the legislative environment of America today.

Join us

If you’ve followed COSL’s work, you know our north star: safer online spaces and robust civil liberties. “Drawing the Line” is how we stay true to both—calling out genuine harm while rejecting dragnet criminalization of fiction, identity, and private life. If you believe that safety and freedom aren’t opposites, they’re partners, we need you with us.

Donate to support COSL’s legal and policy work so we can keep showing up in courtrooms and capitols where these lines are being drawn. Every contribution helps us defend a future where survivors get real support, creators keep creating, and your bookshelf and hard drive stay private.

—

For more on the legal issues we raised, see COSL’s amicus brief in U.S. v. Anderegg (7th Cir. No. 25-1354).